Reading EU law is hard, even for experts – especially if it is cranked out at the current speed and volume.

Inspired by various requests for a brief navigation aid, below my attempt at drawing you a simple map. It will help you find your way around most common types of EU law like directives and regulations. (There are some exceptions like the treaties creating the EU.)

A Simple Map

Most EU acts follow a standard structure – once you can recognise it, everything EU law-related gets easier. The basic order is:

1. Title

2. Preamble (Citations, Recitals, Solemn Forms)

3. Enacting Terms (and Annexes)

This basic structure means that, depending on what you want to know, you do not need to start reading from the top. For example, if you are primarily interested in why and how the EU is acting, you’ll get answers in the preamble. But if you want to get an overview of the new rules that the EU is setting and who is directly concerned, then start with the enacting terms.

Of course, I can’t help but add that it is still advisable to read the whole law, including supporting documents like the impact assessment, if you want to engage meaningfully with it.

In addition, Commission proposals are usually accompanied by an “Explanatory Memorandum”. This is a cover note that briefly sets out the rationale for the legal act, how it fits with existing (EU) policies, and what the proposed law’s likely impacts are. As such, it is very useful, but also the Commission’s side of the story.

1. Title

Take a good look at the title. It holds a lot of useful information to orient yourself:

- It specifies the type of act (e.g., regulation, directive, decision).

- It identifies the institution(s) that adopted the act (Parliament, Council, Commission)

- It highlights whether the act is amending any existing law, and (ideally) lists all the acts that are amended or repealed

- If it is an implementing or delegated act, the title will normally say so

- It includes the date of signature (OLP) or adoption

- It also gives you the reference number of the act, as well as an indication of the broad policy area (EU, Common Foreign and Security Policy, or Euratom)

- Finally, the title outlines the subject/contents of the act. Sometimes there is also a short title that is added at the end (here: “Chips Act”).

Here is the full title of the Chips Act as an example:

2. Preamble

The preamble is everything between the title and what the EU calls the “enacting terms” (the part that actually sets new legal rules).

The preamble has three main elements: citations, recitals and solemn forms.

2.1 Citations

The citations explain why the EU has competence and what procedure was used to adopt the act.

The citations are easy to spot because their language is mostly standardised, usually beginning with “Having regard to …”.

The first citation provides the legal basis of the act, i.e., the provision(s) in the EU treaties that confer power on the EU to adopt this particular law. If the direct legal basis is in secondary legislation, you will find it in the second citation. This is key information because the choice of appropriate legal basis (or bases) determines what the law can legally achieve and how it needs to be adopted – this can be review by the courts if there are disagreements!

The rest of the citations set out the main steps leading to the adoption of the act. For example, this tells you which procedure was used. These are again mostly standardised, as you can see here for the Chips Act:

2.2 Recitals

Now it gets more interesting. The recitals explain the objectives of the act – why the EU thinks it is necessary to create new rules now, and why it chose this particular regulatory approach.

Again, you can easily identify the recitals because of their formatting. Each recital is numbered and they start with the word “whereas”. Newer acts tend to use only one “whereas” at the top to clean up the language, but others still use it to start each recital:

[Recitals continue …]

The key thing to understand is that the recitals still set the scene. They are not the normative part of the act (see Enacting terms below), and therefore also must not sound like they set new rules.

It’s quite vague what the recitals need to include and how detailed this statement of reasons has to be. However, there are a few things that need to appear in the recitals. For example, if the act repeals or deletes existing law, the recitals need to explain why.

2.3 Solemn forms

Think of these as the brackets that hold the preamble together. If you look closely, you’ll see the preamble is designed as one single, very – very – long sentence.

The preamble starts with the relevant institutions “THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION,” – now come all the citations and the recitals – and finally the enacting formula is concluded: “HAVE ADOPTED THIS REGULATION:”

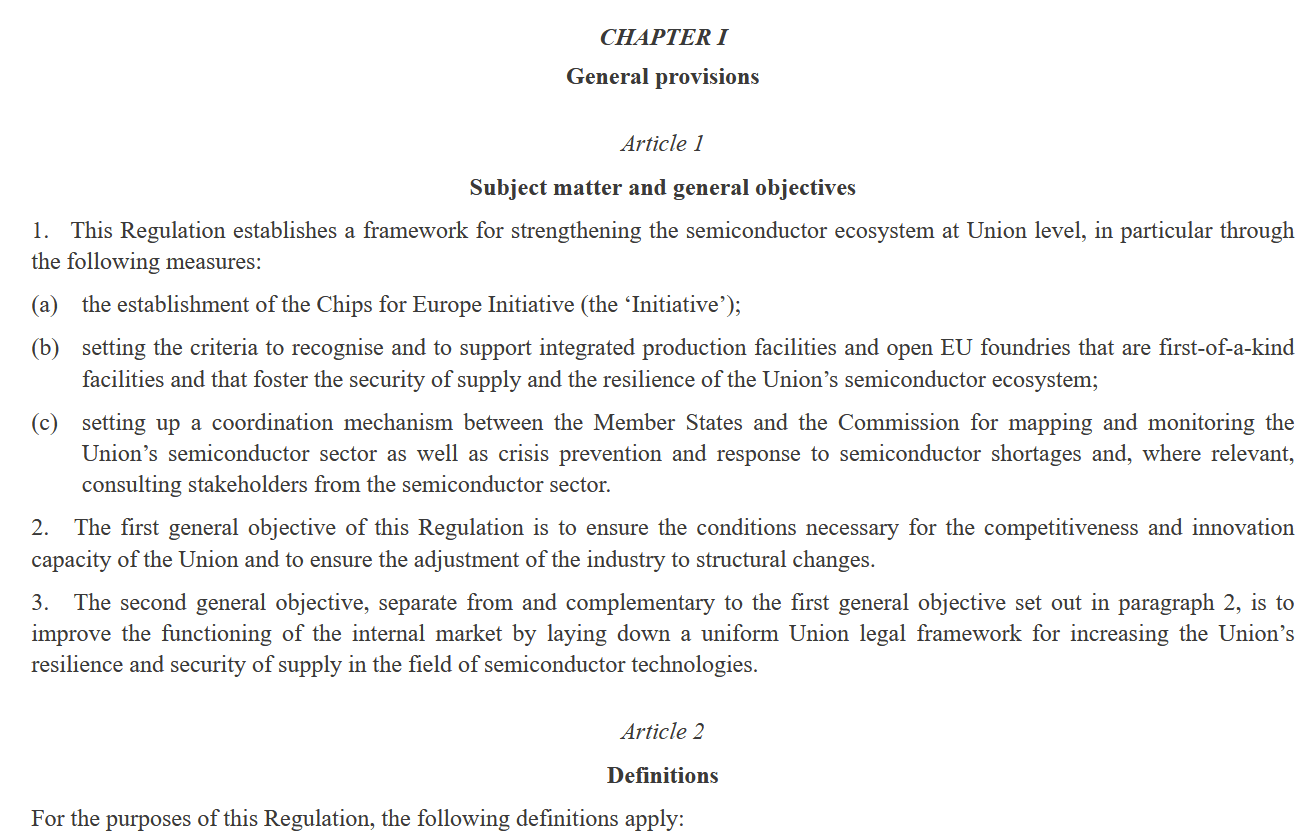

3. Enacting terms (and annexes)

Congratulations. You have found the part of the act that actually sets new, binding rules. (Assuming we are talking about a binding act.) Consequently, articles that only express political ambitions and desires are now out of place.

The enacting terms are composed of numbered articles (these can be grouped into sections, chapters, titles, and parts – in this order) and, where necessary, supplemented by annexes.

Legislative drafters try to follow a standard structure for the enacting terms:

- The first article tends to set out the “subject matter” (what the act deals with, and sometimes also what it explicitly does not deal with) and the scope (the situations and actors it applies to) of the legal act.

- The second article is usually dedicated to definitions of key terms. Definitions are crucial because even though the guidance discourages drafters from introducing “autonomous normative provisions” via the definitions, it’s clear that who defines, decides!

- Then come articles setting new rights and obligations, the truly normative part of the act.

- Provisions delegating or conferring implementing powers

- Procedural provisions

- Articles relating to implementation (e.g., rules and dates for transposition by Member States, penalties, remedies)

- Transitional and final provisions (e.g., amendment/repeal of earlier acts, entry into force, transition periods)

Legal acts can also have annexes, which spell out further technical detail.

I hope you found this useful. If you are desperate for more, take a look at this EU drafting handbook.

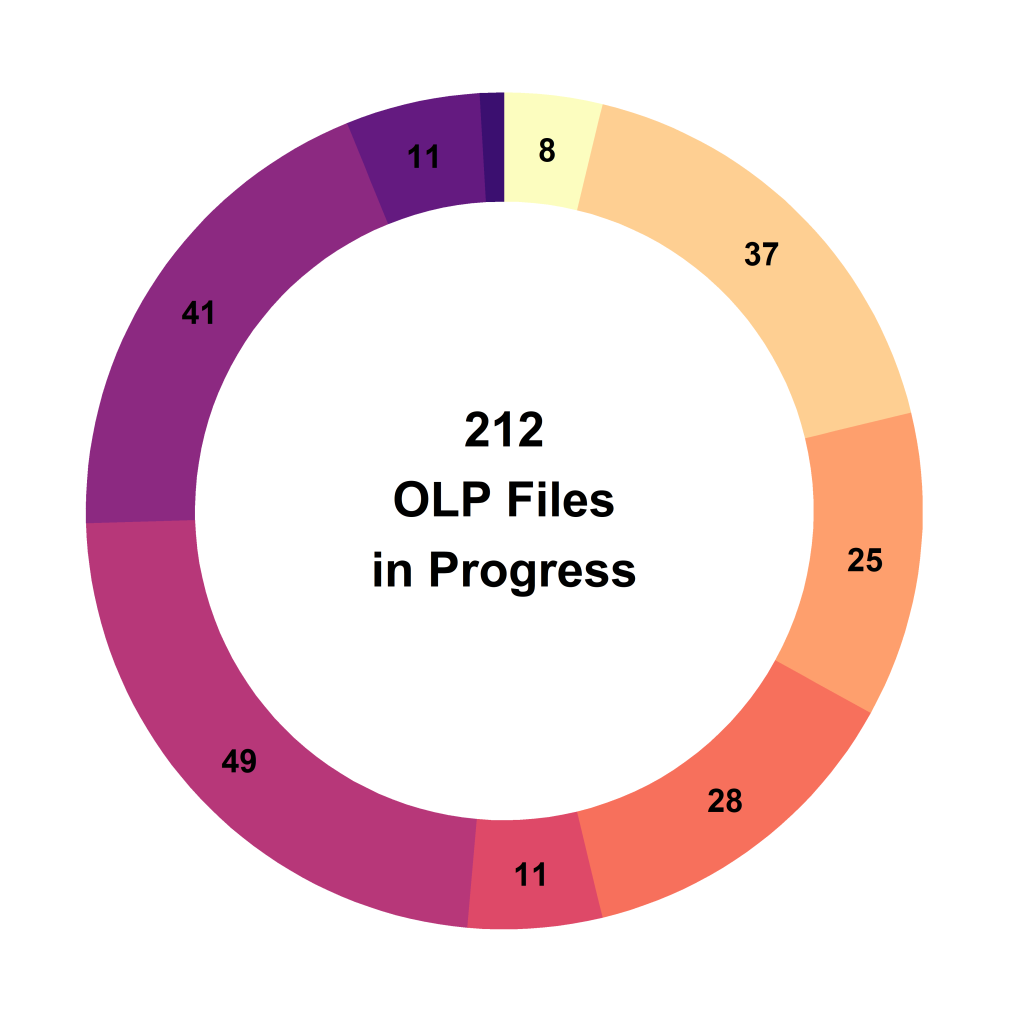

The EU also provides this chart on the structure of its acts: