This post continues my assessment of EU law awaiting adoption before the elections. See the first post with useful background here. Below I explore legislative business across the committees in the European Parliament.

Key points:

1. Responsibilities are distributed unequally, with a few (large) committees doing the heavy lifting on most OLP files.

2. The committees leading on many files still face a substantial amount of work. This includes proposals at the early stages of the legislative process, which will not be adopted before the elections.

3. By contrast, (smaller) committees responsible for fewer files have almost concluded their legislative work, with only few OLP files at advanced stages remaining.

4. The unequal OLP workload and progress across committees raises interesting questions for the plans to reorganise parliamentary committees after the elections.

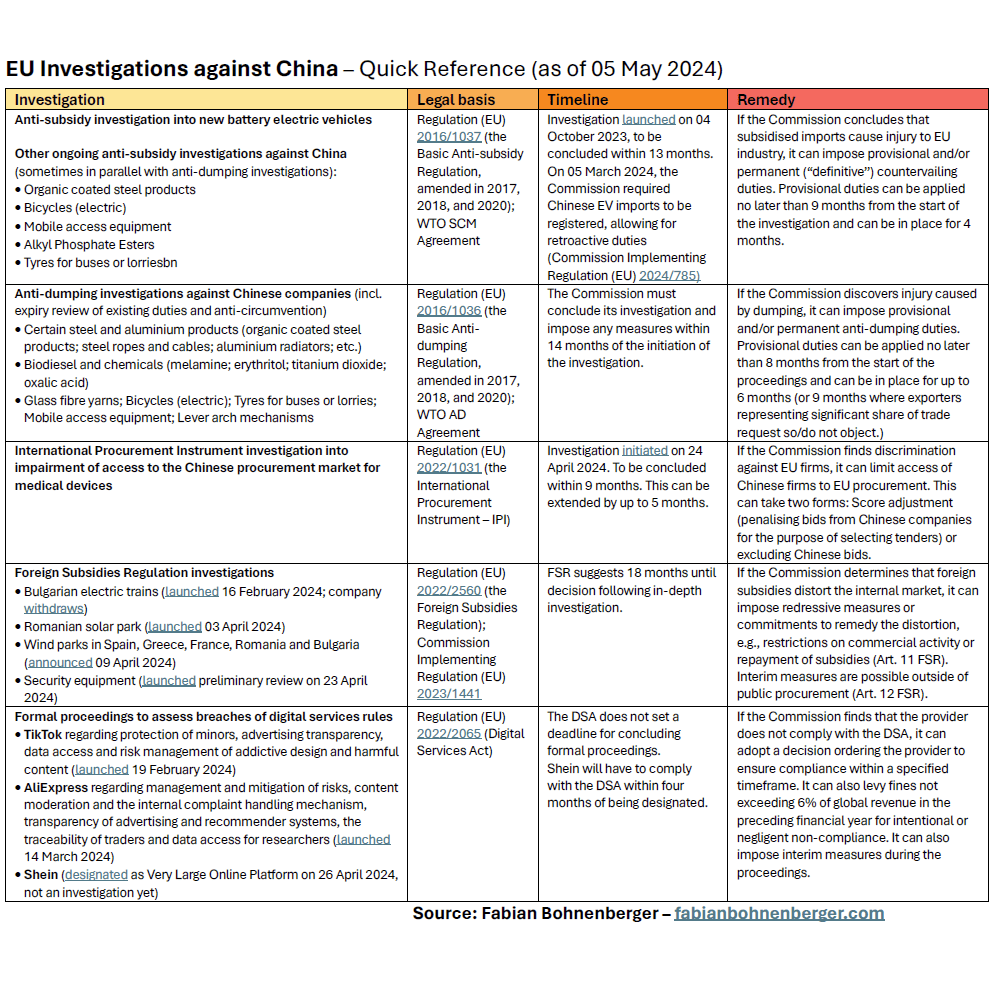

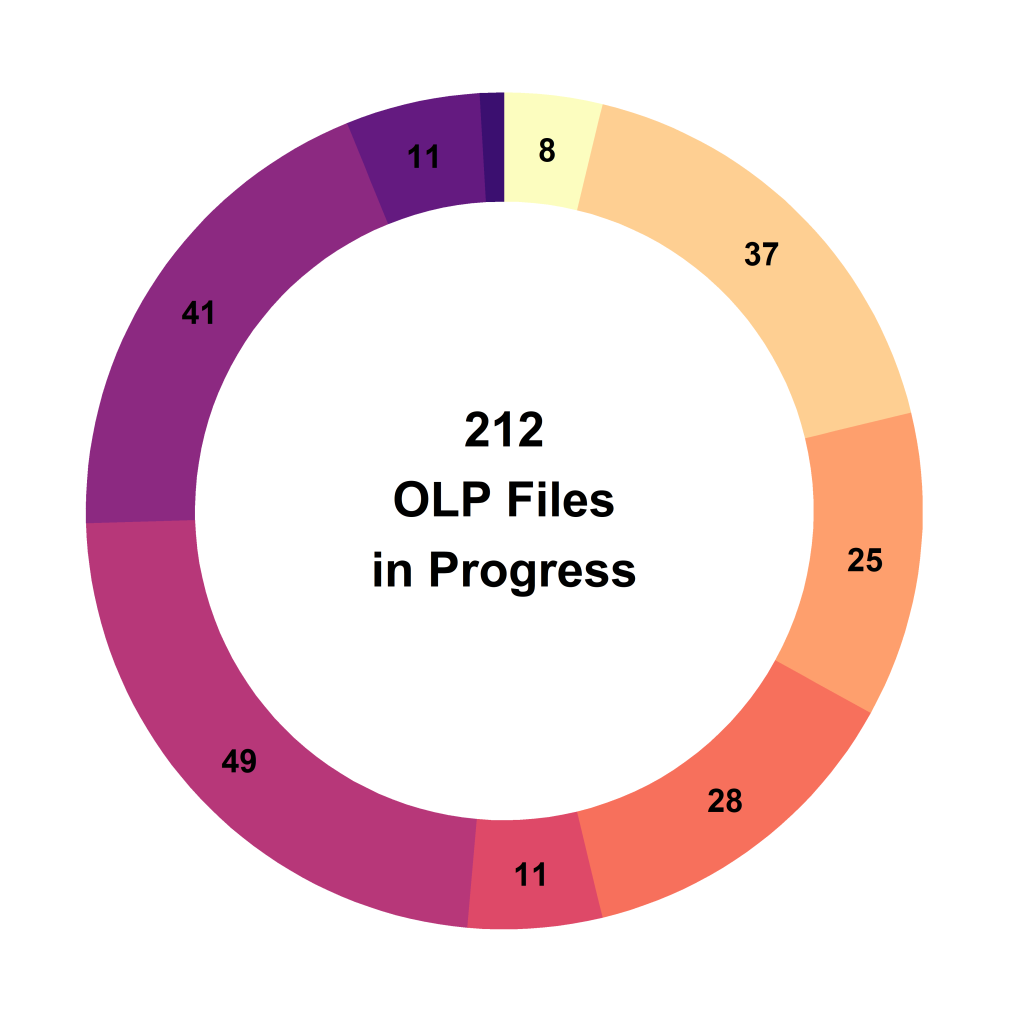

1. Unequal workload

This figure shows for how many OLP files each committee is responsible. It reveals an unequal workload: The two busiest committees, which are leading on over 80 files each, are the Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) and the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) Committees. Their names already suggest their cross-cutting nature.

The heavy workload of ENVI, in particular, should not come as a surprise in the context of the European Green Deal. With 88 members, it is also the biggest committee in the European Parliament. LIBE and Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) are also large committees with 69 and 61 members respectively.

Avoid reading too much into the total counts. Each file and the work it involves is different, so slightly higher file numbers do not necessarily mean busier schedules. But looking at the broad trends, the figure reveals committees with very different OLP workloads.

See for committee abbreviations and number of members here.

2. Substantial work remaining

As explained previoulsy, there are still around 216 files waiting to be adopted. The figure above now shows that most of this work is concentrated in certain committees/policy areas.

There are two main reasons why files remain unfinished: Late arrival of the proposal and delays because political groups could not agree the law.

The ENVI committee illustrates both cases: It received three new proposals on chemicals regulation as late as last month and had to chew over many controversial Green Deal files for the last years, delaying their passage. To avoid further clogging up the legislative pipeline, the Commission even held back some new proposals over recent months.

3. Unexplained differences

As the figure above shows, there are committees that take the lead on OLP files less often. For example, the large Foreign Affairs (AFET) Committee is in charge of very few files because the EU (and EP) still has little foreign policy competence.

However, it seems that some of the smaller, more specialised committees were able to complete a larger share of their assigned files than the bigger, more cross-cutting bodies like LIBE and ENVI.

But it is hard to draw firm conclusions about committees’ performance without delving deeper into the data. A higher share of adopted files could be the result of legislation that is more specialised, requiring less involvement from other, opinion-giving committees. Or perhaps it was less controversial, making it easier to pass.

While the figure above reveals differences between the committees, it cannot fully explain this variation. First, I only include OLP files, not special legislative procedures, which narrows the picture. Second, I only account for lead committee(s), not opinion-giving committees. But I account for joint responsibility under Rule 58 RoP, which leads me to double/triple-count some files in the figure.

4. Plans to reorganise Parliament

Still, it is interesting to consider committees’ different exposure to OLP work in the context of ideas to reorganise Parliament after the elections. The increased complexity of EU legislation has resulted in frequent fights over competence between committees, making it more difficult and time-consuming for Parliament to adopt legislation.

One idea that has been floated is therefore to reduce the number of committees, creating fewer but larger committees with broader responsibilities.

Given committees’ different experiences in this term, it is important to understand whether new cross-cutting committees would streamline the legislative process or create bottlenecks for an even larger number of files to pass through.

Finally, it is useful to remember that although the committees play an important role, there are many other factors determining legislative success or failure within and beyond Parliament.

2 responses to “A Progress Report on Law-Making in the European Parliament”

[…] The final committee report is now available, so I am taking a quick look at the proposed changes and what they will mean for parliamentary business. (For context, I just wrote about Parliament’s legislative work here.) […]

LikeLike

[…] many laws are still awaiting adoption? I updated my calculations – first introduced here and here – to examine where we are at and what progress legislators (Parliament and Council) made together […]

LikeLike