After painstaking negotiations, the EU institutions last week concluded the mid-term revision of the EU’s long-term budget.

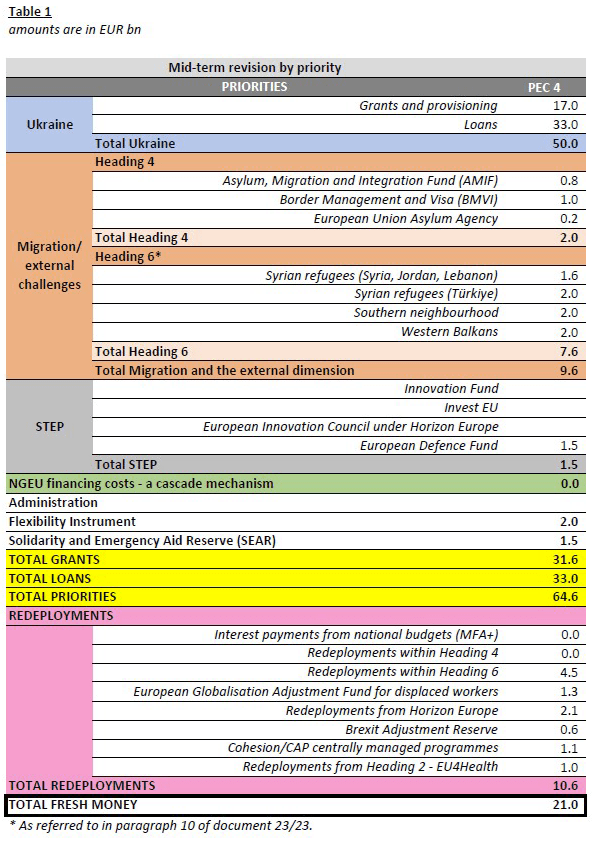

There are different numbers floating around to explain what this revision of the 2021-2027 multiannual financial framework (MFF) means in practice. For example, the Council press release claims that “€64.6 billion of additional funding will be made available to address new and emerging challenges facing the EU”.

While technically correct, the existing budget only receives €21 billion of fresh money. The rest is made up of loans (€33 billion) and redeployments of existing funds (€10.6 billion).

The big headline numbers obscure a few interesting developments. Some key takeaways:

1. Limited additional funds

This first-ever revision of a MFF still adds €21 billion to the EU budget. While this does not sound like much compared to the size of the 2021-2027 budget (slightly more than €2 trillion in total), the top-up represents a hard-fought compromise.

The Commission asked for more than three times that amount to make up for high inflation, rising interest costs and unexpected expenses (Ukraine).

But Member States face the same pressures, which made them unwilling to stump up substantially more cash for the EU budget. Germany – suffering from its own, self-inflicted budget crisis – along with other frugal governments pared down the Commission’s request and demanded redeployments of existing funds to address new priorities.

2. Stable support for Ukraine

Financial support for Ukraine is the centrepiece of the new agreement and as such was excluded from the penny-pinching. The EU will provide €50 billion to Ukraine from 2024 to 2027, consisting of €17 billion in non-repayable grants and €33 billion in loans.

It’s fair to say that this was the politically most significant but also most challenging part of the deal, even though 26 EU heads of state firmly supported incorporating aid for Ukraine into the EU budget. Only Viktor Orban, the Hungarian Prime Minister, opposed this. After coming under intense pressure, he finally relented at a special European Council meeting in early February.

By incorporating Ukraine aid into the budget, the EU places its support on a stable and more predictable footing. This also aims to reassure Ukraine that EU aid will continue to flow over the coming years.

3. Token strategic investment

There’s still no shared ambition for EU strategic investment. Member states only agreed a token €1.5 billion fund for strategic technologies for Europe (STEP).

In a world where Germany on its own – not to mention the US and China – can offer Intel more than €10 billion in subsidies to attract new semiconductor manufacturing, the EU fund will not impress anyone.

This gap in the budget is disappointing and falls far short of the Commission’s call for a new European Sovereignty Fund “to ensure that the future of industry is made in Europe.” (I write here about the EU’s competitiveness agenda.)

4. Higher borrowing costs

High interest rates are a significant new factor in EU budgeting. The resulting increase in borrowing costs is currently estimated at €15 billion between 2025 and 2027.

It is hard to overstate how much the EU’s role in borrowing funds has changed over the last four years: The EU currently has over €400 billion in outstanding liabilities, of which about €370 billion have been issued since 2020. To put this into perspective, the EU debt pile is now larger than that of 21 member states. Only six member states have government debts that are larger than the EU’s liabilities.

The Commission’s role in issuing debt on behalf of the EU grew dramatically with the Covid pandemic, when member states (Germany) overcame their opposition against joint borrowing in the face of an uncertain recovery. This breakthrough led to the creation of the up to €800 billion “Next Generation EU” (NGEU) fund.

But since early 2022, interest rates have risen steeply, driving up borrowing costs for everyone. Rates for 10-year EU-Bonds have increased from almost nothing (0.09%) at the time of the inaugural 10-year NGEU bond in June 2021 to 3.56% in late 2023.

To address this budget squeeze caused by higher borrowing cost, the revision introduces a new “cascade” mechanism. This will ensure that the money to cover interest and coupon payments is always available without the need to cut existing programmes.

Other developments and omissions

The budget revision moves around various other pots of money to address new EU priorities like migration. The table below summarises key changes and allocations.

Finally, new “own resources” – the EU’s income streams – are conspicuous by their absence. The Commission has proposed a set of new own resources, which would come in handy to cover the repayment of NGEU funds over the coming decades. Yet, unsurprisingly, the discussion has been slow-going between Member States.