This is the second post in a series where I explore the EU’s legislative process using data from the past five years. Don’t worry if statistics or EU procedure sound intimidating – I’ve written this in a way that requires little knowledge of either.

I recommend you start with part 1.

When you think of the EU’s legislative process, “speed” likely isn’t the first word that springs to mind. The Ordinary Legislative Procedure (OLP), which guides most EU law-making, typically takes around a year and a half – sometimes substantially longer – as I show in part 1.

But did you know that some laws defy this timeline, moving from proposal to entry into force in just a few weeks, or even a few days? Take, for instance, the emergency response to the Covid pandemic, the rapid approval of financial aid to Ukraine, or legislation to manage post-Brexit relations with the UK.

In this post, I consider a group of 106 files, which represents about one in four laws passed via the OLP procedure in the last five years. These fast-tracked laws share two key traits: they were more urgent and/or less controversial than other files. In practice, this meant that the usual lengthy negotiations between the Parliament, the Council, and the Commission (known as trilogues) were cut short or bypassed entirely, with Parliament and the Council accepting the Commission’s proposals with few, if any, amendments.

The simple way to adopt a law

This special case is a great way to start exploring the legislative process because we avoid the complexity of additional trilogue steps (which I’ll focus on in the next post).

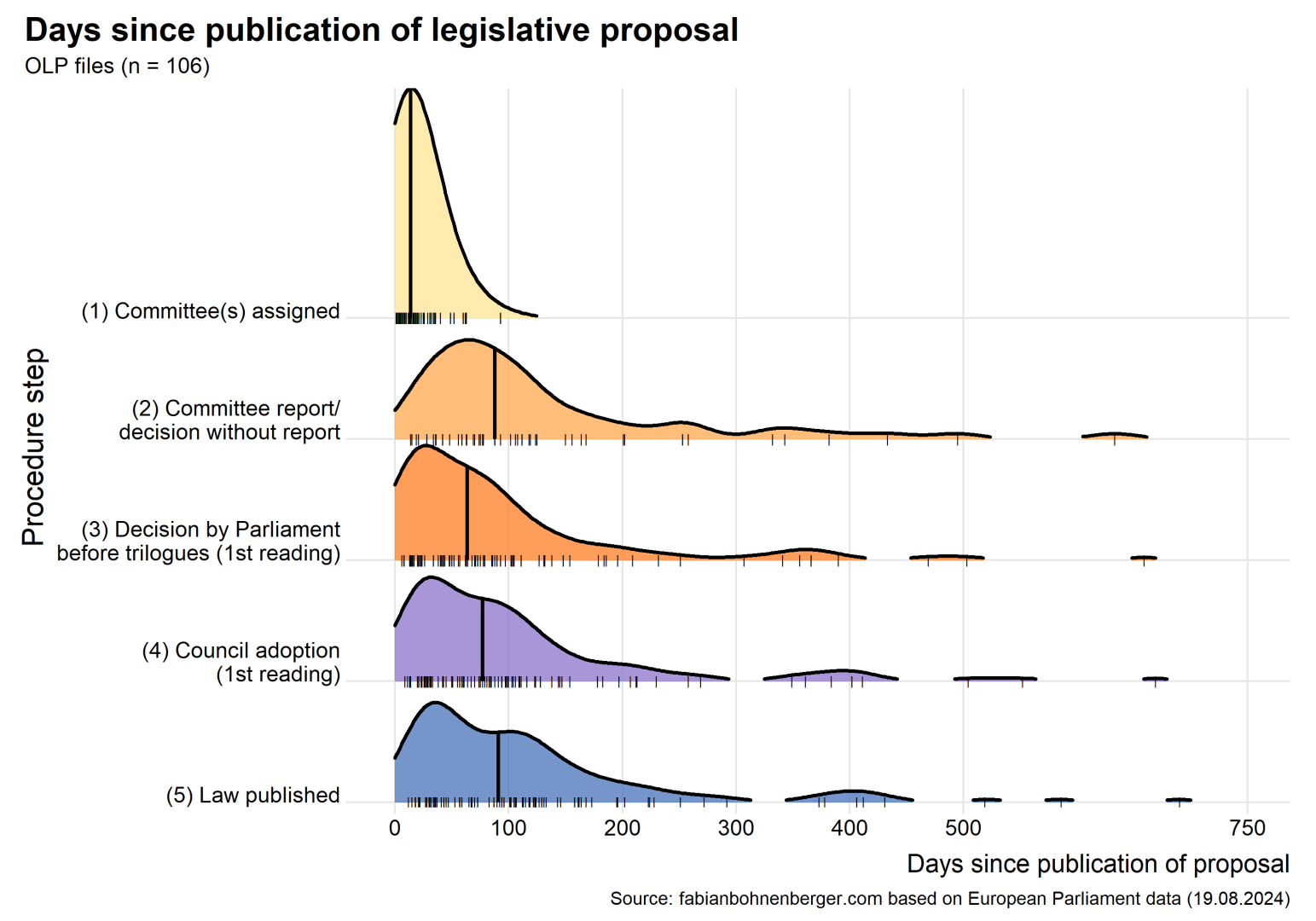

This is how the process looks for this subset of 106 laws – again, I only focus on some key events, this is not comprehensive:

Compared to the figure showing all 548 files (see here), three things stand out:

- There are fewer stages because the files we are now concerned with required little negotiation – both within and between the Parliament and the Council.

- There are fewer observations at each stage because we consider fewer laws than in part 1. I am also excluding unfinished files here. This pushes the peaks of steps 1-3 slightly to the left, but it reduces interference from other proposals that remain at an early stage.

- Legislators adopted most of these files quickly. I am able to halve the timeline on the horizontal axis compared to the figure in part 1. (And the high values here relate to codification – a special case of EU law-making – see below.)

Let’s consider each step through the eyes of EU lawmakers:

1. Committee(s) assigned

One of the first things that Parliament does with a new legislative proposal is assign it to one or more of its committees. This usually happens quickly – half of all OLP files had a home within 46 days from publication of the proposal.

In the subset of 106 laws, half were assigned within just 14 days.

2. Committee report/decision

Once the responsible committee has discussed the proposal, it usually adopts a report with amendments. Across all OLP files, committees make half of these decisions within 253 days, around 8 months.

A special caveat applies here because our subset contains files that Parliament adopted via its “urgent procedure”. For example, Parliament did not wait for a committee report to grant financial assistance to Ukraine or other countries in need. It also didn’t delay authorising EU/UK fishing vessels to operate in each other’s waters, etc.

For the 106 files, the data only records 52 reports, half of which were issued within 88 days. The mismatch in the number of observations explains why the median is further to the right here than at the later stages.

3. Decision by Parliament (before trilogues)

The proposal now reaches the plenary. Parliament has essentially two options if it wants to pass the draft law:

- Adopt its 1st reading position on the draft (based on the committee report) and immediately send its position to Council.

- Adopt the proposal with amendments and refer it back to the relevant committee for trilogues.

This post focuses on option 1, which is normally used for proposals where neither the Parliament nor the Council want to make significant changes to the Commission proposal. (There are other reasons Parliament might use it, but we are not getting into these here.) I’ll cover option 2, the path for laws that require detailed negotiations on the text of the final law, in the next post.

Half of the laws in our subset are adopted by Parliament within 64 days. This is extremely fast. By comparison, the median for files that are handed back to committees for trilogues is a leisurely 507 days. In both figures, however, the tails stretch to the right. This means it takes the other half of proposals (substantially) longer.

4. Council adoption

The Council can only adopt its official position once Parliament has transmitted its views. For the laws we are considering, there is usually little delay. Half were adopted within 77 days, just two weeks after Parliament.

The sequencing of Parliament and Council adoption is visible in the matching ridgelines.

5. Law published

The final step. The law is published in the Official Journal. Most OLP files – I have publication dates for 390 – appear in the lawbooks over one and a half years after the initial proposal.

For our subset it is obviously much sooner: half are published within only 91 days.

In addition, the five highest values here all relate to laws undergoing “codification”. This is a technical process to unify an existing law and its subsequent amendments into a single new act. It is different from passing other proposals because codification does not allow legislators to make substantive changes to the existing law.

Speed matters

These examples demonstrate that EU lawmakers, despite the complexity of the process, can move quickly – provided that certain conditions are met.

This insight challenges the assumption that EU law-making is always a slow-moving process with numerous opportunities to engage legislators; in reality, shaping laws (even those that take more time) requires careful preparation.

Moreover, we should not assume that the unique circumstances behind these laws eliminated the role of politics in law-making. Events like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine certainly sharpened minds, but the swift passage of many laws is largely due to the fact that the crucial consensus-building occurred before the proposals were even introduced. As such, we might conclude that speed matters in law-making, but so does how it is measured.

4 responses to “The Rhythm of EU Law-Making (Part 2)”

[…] This series explores the EU’s legislative process using data from the past five years. I recommend you start with part 1 and part 2. […]

LikeLike

[…] Part 2 focusing on urgent laws and special cases […]

LikeLike

[…] the next post, I will present the first detailed timeline for a group of urgent and relatively […]

LikeLike

[…] EU’s legislative process and build a timeline of its key steps based on a large dataset. (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, summary & […]

LikeLike