The final EU Environment Council meeting of this mandate fittingly involved some drama to push one of the most controversial Green Deal laws across the finish line. The star of the show was Austrian Environment Minister Leonore Gewessler (Greens), whose vote secured the necessary margin to pass the Nature Restoration Law.

Gewessler defied the declared position of her coalition government. Just a day before the vote on 17 June, the Austrian chancellor had announced Austria’s intention to abstain. So, whose vote counts? And did the Council ultimately adopt the contentious law?

The decisive vote

The razor-thin majority in favour of the law makes this a great case to explore the voting rules in the Council, the EU’s upper house in a bicameral legislature if you will, where national Ministers meet to discuss and agree EU legislation.

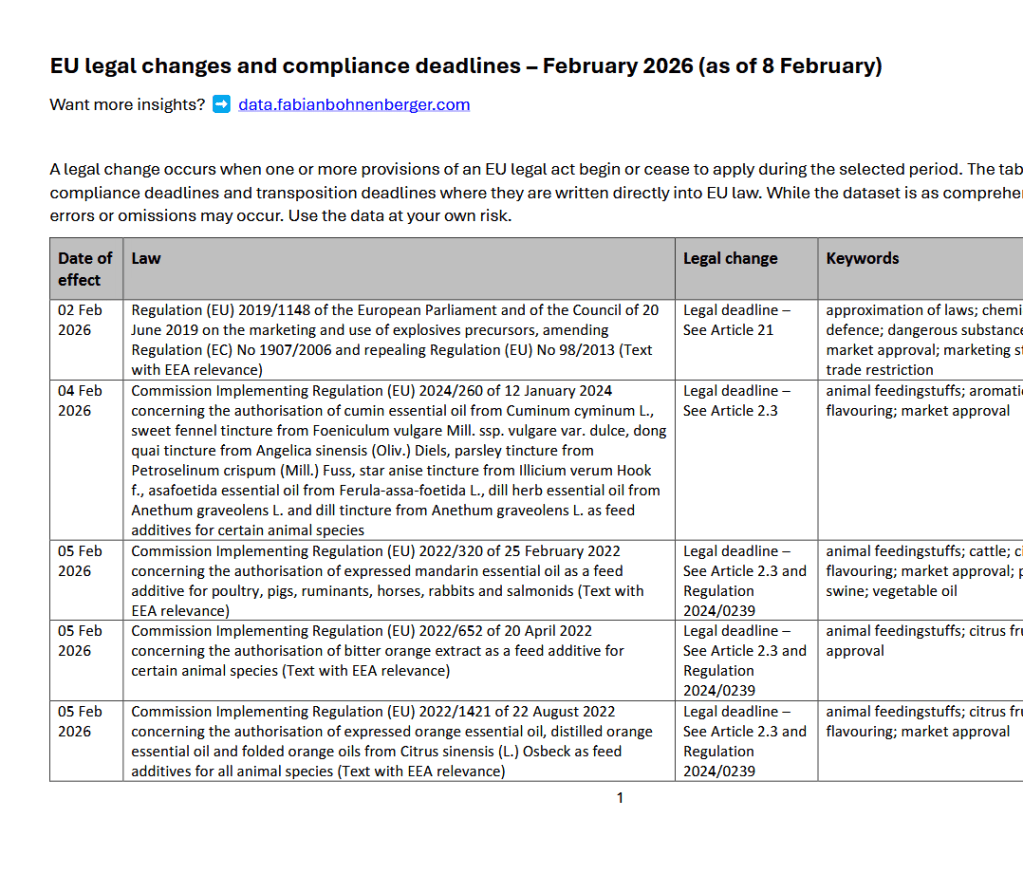

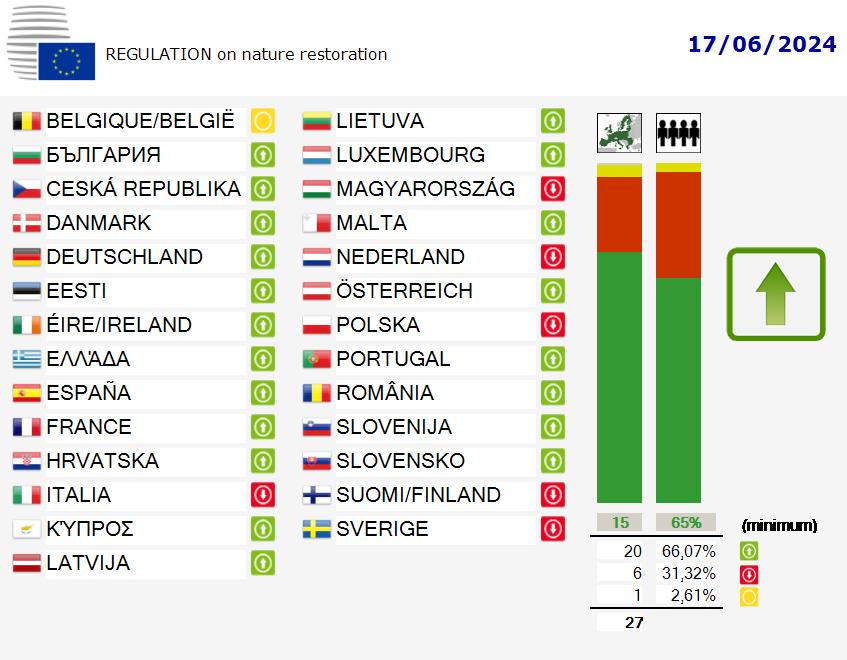

The Nature Restoration Law was adopted using qualified majority voting (QMV), which requires 55% of Member States (15 out of 27) accounting for at least 65% of the EU population to vote in favour of the legislation.

While 20 Member States voted in favour, they together represent 66.07% of the EU’s population. Austria’s vote counts for 2.02 percentage points, making it crucial to get over the 65% threshold.

Who votes in Council?

Let’s start with the legal requirements in the EU treaties regarding who can represent Member States in the Council. The key provision, Article 16(2) TEU, states:

“The Council shall consist of a representative of each Member State at ministerial level, who may commit the government of the Member State in question and cast its vote.”

This places two cumulative conditions on Member States: First, the representative must be at ministerial level. Second, the representative must be able to commit the government of the Member State, i.e., they act not in their personal capacity but on behalf of their government (also see Art. 10(2) TEU on this).

Did Gewessler meet these requirements?

To understand whether Gewessler had the right to cast Austria’s vote in the Council, we need to answer whether she met these conditions under EU law.

As to the first criterion, Federal Minister Gewessler has represented Austria in the Environment Council since 2020 as its registered representative.

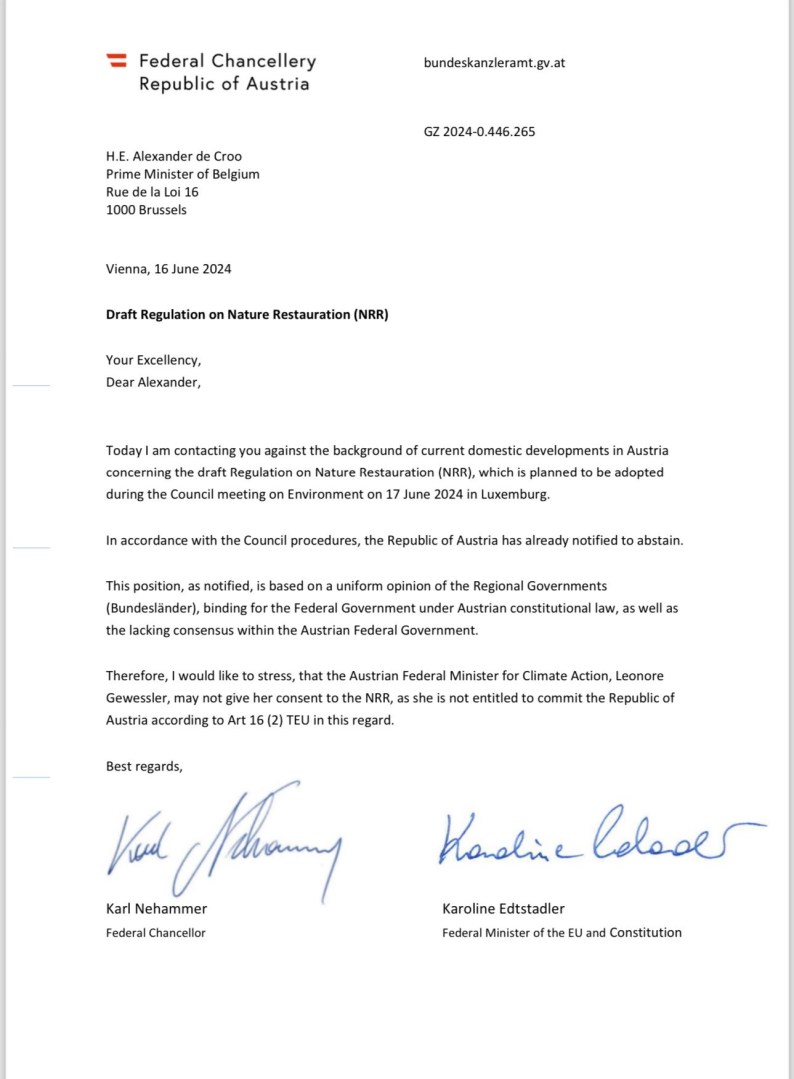

But did she have the authority to commit Austria? Just a day prior to the vote, Austrian chancellor Nehammer wrote to the Belgian Presidency of the Council, announcing Austria’s intention to abstain and stating that Gewessler “is not entitled to commit the Republic of Austria.” (See first letter copied below.)

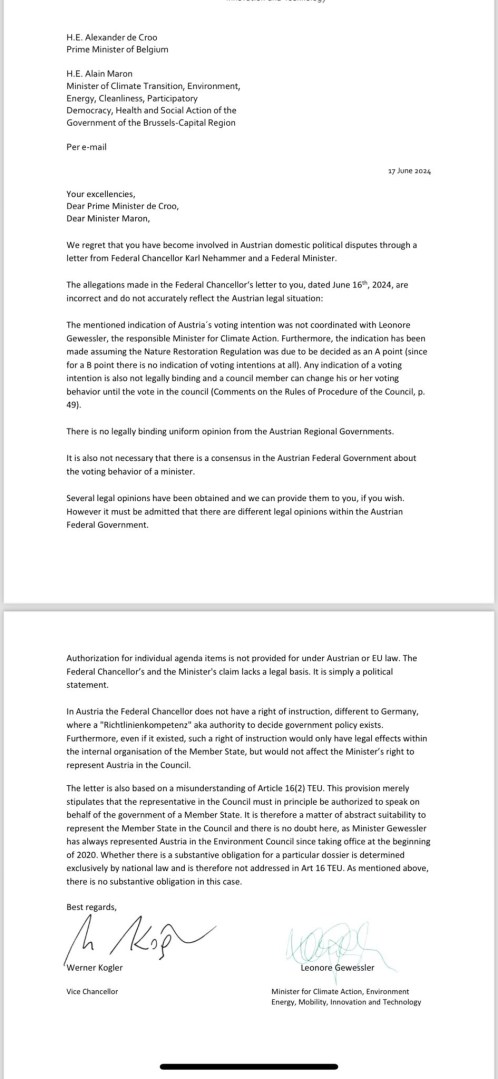

By contrast, Minister Gewessler argues that the second condition in Art. 16(2) would demand from representatives only an “abstract suitability to represent a Member State in the Council” like the one that enabled her to participate and vote in the Environment Council so far. (See second letter copied below.)

Who is right?

Neither Article 16(2) TEU, nor the Council Rules of Procedure require specific authorisation for Ministers to cast individual votes. They only stipulate that a Member State needs to be represented by a competent Minister. It is a matter of national law to define who this competent (read: with the authority to commit their government) Minister is. Council’s Rules of Procedure say as much:

“It is for each Member State to determine the way in which it is represented in the Council, in accordance with Article 16(2) of the TEU.”

This means Council representatives might be bound by additional domestic requirements, constraining their voting behaviour, but these national rules are separate from EU law. I will not delve into Austrian domestic law here.

Consequently, votes that are passed in (potential) breach of any national requirements of a specific Member State remain valid at the EU level. There are good reasons for this: Verifying compliance of each Minister’s vote with their national law before each vote would be impractical and render the Council dysfunctional. To allow the Council to make decisions, which sometimes means agreeing last-minute compromises to secure necessary majorities, requires representatives that are empowered to commit their Member States, even on contentious issues.

This also answers another issue raised by the chancellor’s letter: Can a government “vote by mail” and thereby bind their Minister to a position in the Council meeting? Governments can and often do communicate their voting intentions in advance. But it is still up to the attending Ministers to cast the final vote.

Next steps

While the Nature Restoration Law is now close to completing its fraught journey through the EU institutions, the political fallout is mostly limited to Austria. The coalition seems to have survived the vote, but the Green’s partner, the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), said they would seek annulment before the Court of Justice of the EU. However, they are unlikely to succeed because the Court will base its decision on the relevant EU treaty provisions, mainly Article 16(2) TEU.

Finally, it is not uncommon for Ministers to be torn between their personal beliefs and instructions they receive from capital. While few openly defy their own government, what Ministers say in Council and how they vote occasionally varies to reflect this tension. For example, the German representative recently expressed his personal support for the platform work directive but abstained because of disagreements within the German coalition government.

As the saying goes, a good diplomat is someone who can deliver a no in such a way that it feels like a yes – Minister Gewessler took that quite literally.

Letters to the Council Presidency