A bit of holiday reading inspired this brief review of a new book by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner titled “How Big Things Get Done. The Surprising Factors Behind Every Successful Project, from Home Renovations to Space Exploration”.

Flyvbjerg, who has spent decades studying and advising on megaprojects, uncovers some of the main pitfalls of project management and offers a set of heuristics for better leadership. His advice is useful for projects of all shapes and sizes, but the book mostly draws on his experience with very large projects (be it infrastructure, IT or the Olympic Games). Across most of these categories, he finds “average practice is a disaster, best practice an outlier.” Most of us would probably have guessed as much. But the numbers are still startling: Of more than 16000 projects in his dataset, only 8.5 percent came in on time and on budget – and delays and cost overruns can be huge!

What makes the book’s approach stand out is that Flyvbjerg explores the practical knowledge of experienced project leaders, highlighting lessons these masterbuilders have learned over a long career that make them successful. This is not easy to do – as I know from my PhD research on diplomatic practice, asking practitioners to explain why they do certain things in certain ways can feel like asking fish to describe the water in which they swim. But Flyvbjerg succeeds in teasing out some key heuristics for project management that, among other things, place emphasis on proper planning, experimentation, risk mitigation, and scalability.

Perhaps because of this hands-on perspective, the book pays relatively little attention to the political level. Flyvbjerg acknowledges the decisive role that political dynamics can play in determining the success or failure of big projects. He even cites Robert Caro’s superb analysis in The Power Broker. However, How Big Things Get Done does not really tackle the hard question how the key decision-makers can be made to follow Flyvbjerg’s advice in order to overcome counterproductive behaviour. This includes lowballing the costs to get projects approved, selecting inexperienced but local project leaders, committing to projects after only superficial planning, and throwing good money after bad once a project has come off track. It might be too much to expect an answer to this fundamental challenge, but our own experience as well as Flyvbjerg’s analysis suggest that we cannot just rely on the force of the better argument where power, psychology and large amounts of (public) money are at play.

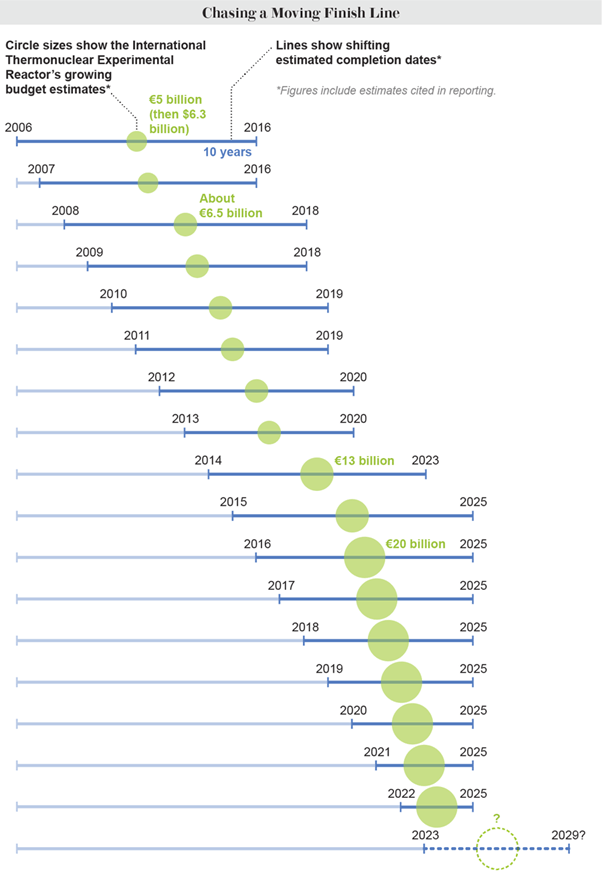

Not to pick on any particular project, but this great illustration of the travails of ITER (the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor in the south of France) came to mind while reading the book. It might be very silly to expect a clear delivery schedule for an international project aiming to build a small star on Earth, and construction of the giant fusion power machine has unsurprisingly been beset by delays. A recent article concludes, “ITER is on the verge of a record-setting disaster as accumulated schedule slips and budget overruns threaten to make it the most delayed—and most cost-inflated—science project in history.”

But no matter the size of the challenge (Flyvbjerg applies his advice to everything from wedding cakes to climate change), How Big Things Get Done is well worth a read to prepare for any project.

(And just in case you want to catch up on nuclear fusion projects, Arthur Turrell’s The Star Builders offers a great overview, although he wisely doesn’t cover ITER much.)