This posts summarises preliminary results of my analysis of treaty commitments in the African Union. The assessment is part of a research project for the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that explores the behaviour of authoritarian countries in the African continental integration project more generally. More in our forthcoming article “Rigging is better than Coups”: Why Authoritarian Regimes in Africa Commit to Continental Democracy Provisions

For the member states of the African Union (AU) and its predecessor, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the adoption of treaties and protocols constitutes a central vehicle for continental integration. The realisation of the organisation’s policy goals fundamentally depends on the political will of its member states, which expresses itself in governmental decisions to sign and ratify these legal instruments. This post shows the considerable variation in states’ commitments as witnessed in the act of OAU/AU treaty signature and ratification. Our forthcoming article specifically explores the relationship between a state’s level of democracy and its likelihood to support the continental integration project by signing and ratifying OAU/AU treaties.

OAU/AU Treaties, Conventions, Protocols & Charters

The AU officially lists 61 OAU/AU treaties, conventions, protocols and charters that were adopted between 1963 and 2018. Twenty-three of these treaties were adopted under the auspices of the OAU between 1965 and 2002; the remainder, which also includes protocols amending earlier treaties or new revised treaties intended to replace existing OAU agreements, has been adopted by the AU since 2002. Official data on signatures and ratifications is available for 59 of these legal instruments; these lists were last updated by the AU on 15 June 2017 (excluding the two agreements adopted in 2018).

With only few exceptions, OAU/AU treaties explicitly provide for member states to express their consent to be bound by signature subject to ratification or other form of national approval. The ratification of OAU/AU treaties is critical to ensure compliance with the diverse treaty obligations that AU member states have assumed; an AU treaty is nothing more than an expression of the member states’ aspirations until it is ratified and becomes binding. Most treaties define a minimum threshold of signatures or ratifications that are necessary for a treaty to enter into force for the acceded member states.

Interestingly, only half (30 out of 61) of all AU legal instruments have entered into force and two additional treaties are currently in force provisionally. However, it is important to point out that 18 legal instruments have been adopted since mid-2014, which leaves states little time for signature and especially ratification. While member states have to weigh the status of the treaty as binding domestic law as well as a source of external obligations following its ratification, the AU lacks the power to compel member states to ratify, domesticate and comply with treaty provisions.

African states have adopted more treaties as members of the AU within the last 15 years than they had adopted as OAU member states over a period of almost 40 years. However, the accelerated pace of treaty adoption under the AU does not in itself suggest a significant increase in substantive international lawmaking by the new continental organisation. Treaty-making under the aegis of the AU benefited from preparatory negotiations in the OAU, which laid the groundwork for treaties adopted in 2002 and 2003. In addition, many instruments adopted since 2002 constitute revisions or amendments to earlier treaties or represent more fine-grained additions to existing framework agreements.

The AU does not offer an official classification of its legal instruments by policy area. To allow for better comparison, I subdivide all 61 legal instruments into seven broad categories. My approach adapts an existing classification in Maluwa (2012), but puts additional emphasis on legal instruments aimed at promoting democracy and good governance. Table 1 summarises the classification.

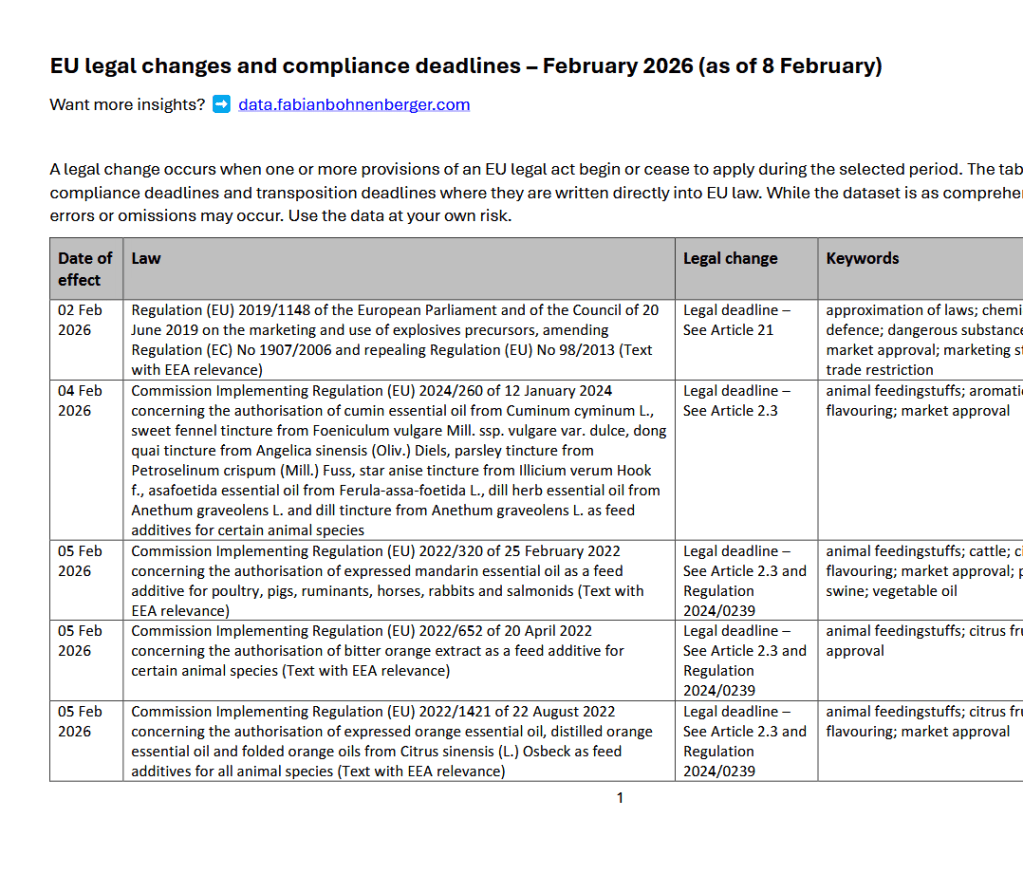

Table 1 – Number of OAU/AU Treaties and Protocols by Policy Area

| Policy Area | Number of Legal Instruments |

| Foundational Legal Instruments and Institutions | 10 |

| Democracy and Good Governance | 3 |

| Human Rights and Refugees | 10 |

| International Security and Crimes | 7 |

| Trade, Economic and Technical Cooperation | 24 |

| Environment | 3 |

| Culture | 4 |

| Total | 61 |

Overall Progress

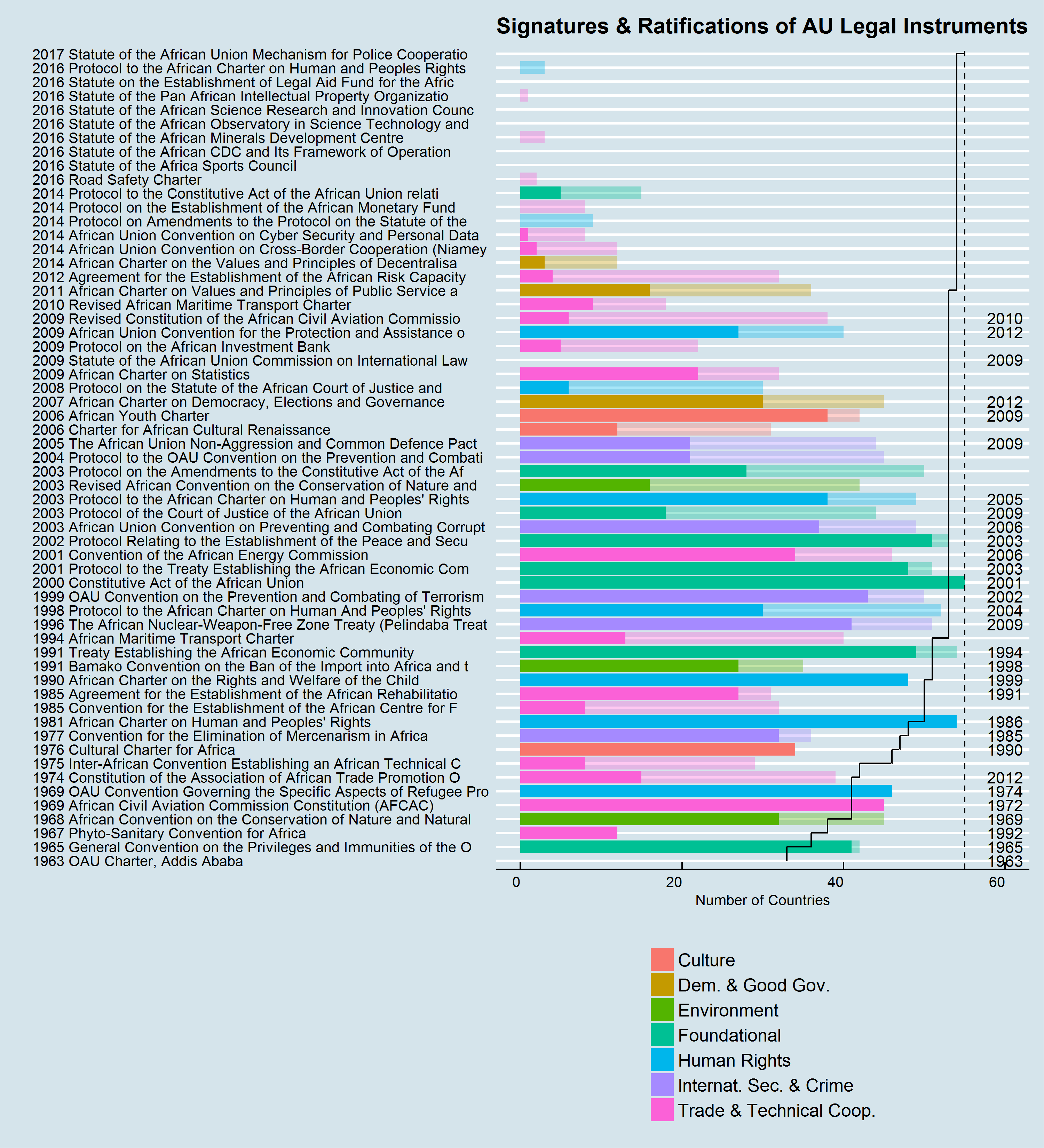

The official records present a rather uneven and slow process of treaty signature and ratification by the member states. Figure 1 summarises the overall development of the legal landscape in the OAU and – starting with the 2000 Constitutive Act of the African Union – the AU. The figure shows signatures and ratifications for each instrument in chronological order. The transparent part of each bar depicts the total number of signatures and the more deeply coloured section shows the number of ratifications. The black lines indicate the rise in the number of OAU/AU member states over time as well as the current cap, which represents the 55 states on the African continent, which are all AU members.

The column on the right indicates the year in which the respective treaty or protocol formally entered into force; blank spaces suggest that the instrument has not yet entered into force. This does not include treaties that only provisionally entered into force, namely the 1974 Constitution of the Association of African Trade Promotion Organizations (in force since 2010) and the 1994 African Maritime Transport Charter. In addition, the 2009 Statute of the African Commission on International Law entered into force without the requirement of signature or national ratification and there is no data available for the 1963 OAU Charter – although it seems safe to assume that all OAU members have ratified the foundational agreement.

Figure 1 – Signatures & Ratifications of AU Legal Instruments By Policy Area

Source: own compilation // Note: I had to cut off the names of most treaties after 60 characters. The two 2018 treaties are not included in the analysis.

Who supports regional integration?

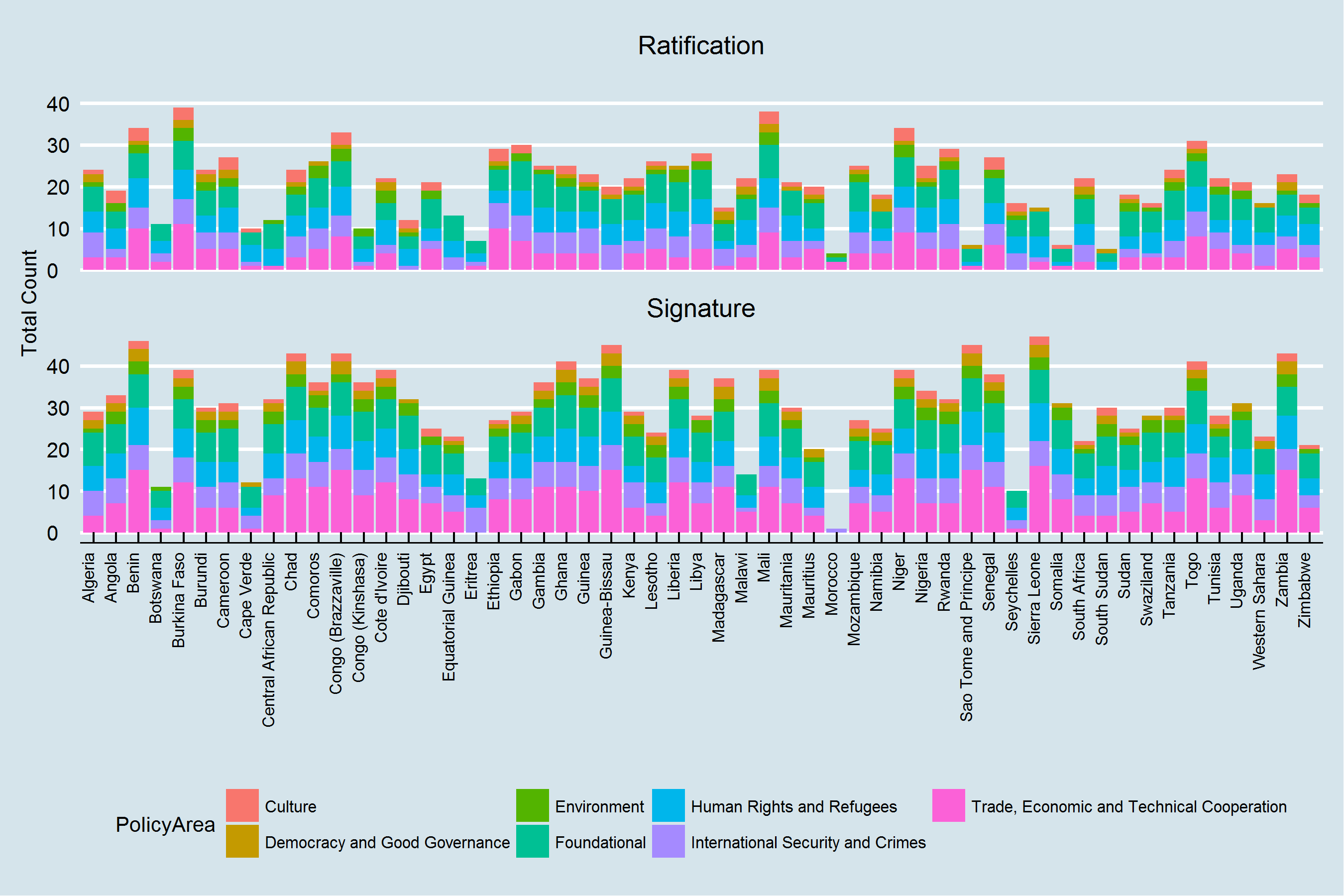

The number of signatures and ratifications of OAU/AU legal instruments varies significantly across member states. In addition, the number of signatures does not necessarily correspond closely with the number of ratifications for any given country; a country which signed numerous treaties might only have ratified few – Sierra Leone is a good example. (See Figure 2) In almost all cases, the number of ratifications remains significantly lower than the number of signatures – an exception is Morocco, which re-joined the AU in 2017 after an absence of more than 30 years.

Figure 2 clearly illustrates that only few member states have signed and also ratified a majority of the existing protocols and treaties. These include Benin, Burkina Faso, the Republic of the Congo, Mali, Niger, and Togo. Other member states have signed but not yet ratified more than half of all agreements. In comparison, a relatively small number of states have signed less than 20 treaties. Only Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, and the Seychelles fall into this category – although ratification numbers are higher for some of these states. This group excludes South Sudan, which was only established in 2011 but has already signed more than half of all legal instruments; Morocco also is a special case because it re-joined the AU this year.

Figure 2 – Signatures and Ratifications By Country and Policy Area

Source: own compilation // Note: does not include the two 2018 treaties

Are democratic countries more likely to support regional integration?

A particularly interesting question is whether the national level of democracy could affect the willingness of African states to support the continental integration project. It has often been theorised that authoritarian regimes shy away from binding international commitments and sovereignty transfers. Following this assumption, authoritarian governments’ strategy for regime survival might discourage them from supporting integration, which should mean that less democratic states are less inclined to sign and ratify OAU/AU agreements.

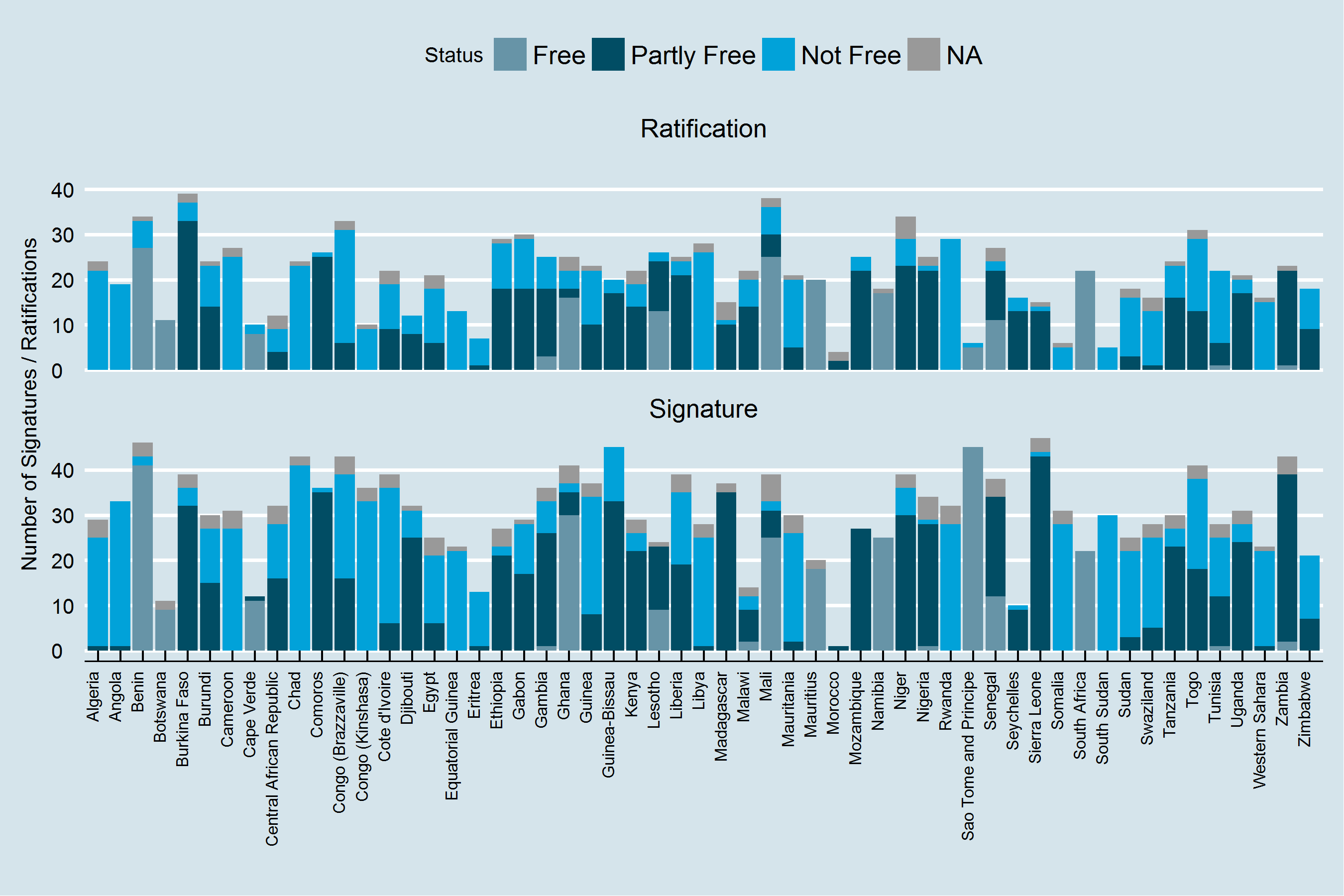

The following analysis is based on the Freedom House classification, which rates a country as either “free”, “partly free”, or “not free”. Because these categories represent a rather crude subdivision of the varieties of African regimes, I will complement this initial look at the data with a more detailed assessment based on more advanced regime categorisations – some of which I introduced here.

Assessing the relationship between a country’s level of democracy and willingness to support regional integration faces one particular problem: frequent and rapid changes in the level of democracy for individual African states over the last decades. While many African countries have moved closer to democratic governance, the path to democracy has not been too smooth. It is therefore necessary to link signatures and ratifications dynamically to the particular circumstances in a country in the year the particular action was taken. Figure 3 offers this information by showing the number of OAU/AU treaties each country signed or ratified based on the Freedom House classification of the relevant country in the year of signature or the year of ratification of the respective treaty. Because Freedom House data is only available from 1972 onwards, all signatures and ratifications made before this date remain unclassified (coded as ‘NA’).

Figure 3 – Freedom House Classification of AU Member States at the Time of Signature / Ratification of AU Legal Instruments

Source: own compilation

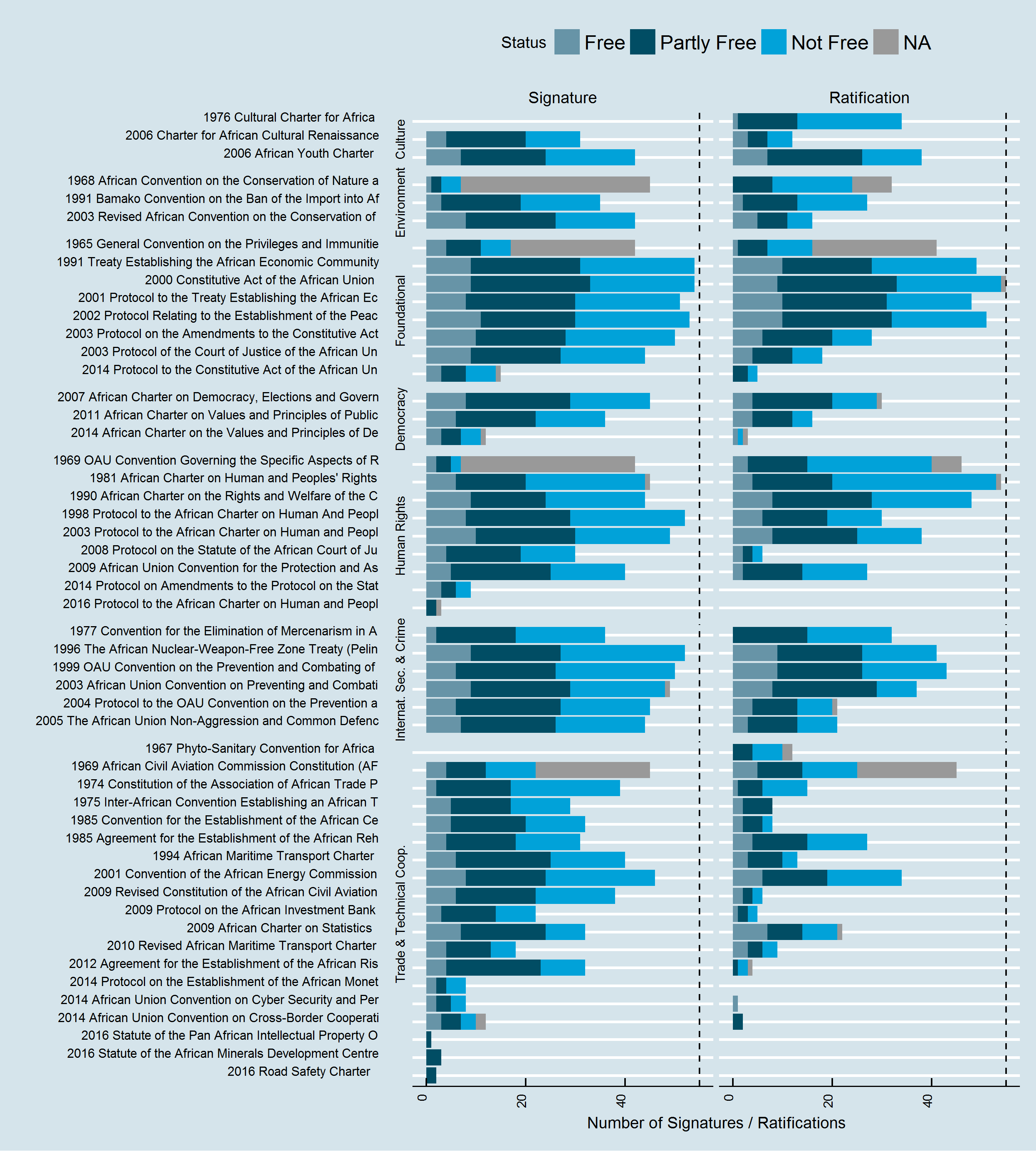

Figure 4 adapts this differentiation and shows the same data for individual treaties; it also distinguishes between policy areas. What becomes clear is that there certainly is some variation in the number of signatures and ratifications between country groups and policy areas. The graph also shows that signatures and ratifications in the democracy category remain relatively low compared to overall committment in other categories; an observation which will be explored further below. Variation seems largest in the broad category for trade and technical cooperation, in which overall committment is especially low. This might, among other factors, also be due to competing regional integration in the economic area.

Figure 4 – Freedom House Classification of AU Member States for Individual AU Instruments

Source: own compilation // Note: figure only shows legal instruments with at least one signature or ratification

Part II available soon … And more in our forthcoming article “Rigging is better than Coups”: Why Authoritarian Regimes in Africa Commit to Continental Democracy Provisions